This post is part of a series taken from research conducted for my upcoming book. Writing is my happy place. If you want to be notified of future stories like this, you can sign up to our newsletter.

Any feedback on the content would be appreciated in the comments below!

The Forgotten Story of the Blues

Part of the premise of my book is that buskers would have more friends and fewer enemies if it were known just how much our culture owes to street performance. Instead, as the historical importance of busking has been overlooked, ignored or even actively hidden for centuries, we now live in a world where councils, business improvement districts and urbanists can effectively destroy busking ecosystems with impunity. After all, what’s the big loss?

To demonstrate busking’s cultural impact, I began by reading up on the story of the blues. I started there because it was a story I thought I already knew. I’ve been told it before, several times in fact. It goes like this:

In the 1940s, blues-playing street performers plugged into amplifiers so that they could be heard over the ambient noise of the busy Maxwell Street Market in Chicago. In doing so, they popularised the sound of the ‘electric blues’, the predecessor of rock and roll. Ergo, it’s thanks to buskers that we have rock music.

It’s a great story. But in researching this book I soon learned that it almost entirely misses the point. Buskers didn’t enter the picture in the 1940s. They’d been a pivotal part of the blues story from the very beginning. Indeed, without buskers—and the ability to freely busk—it’s quite possible the blues would never have gone further than a few juke joints in the Mississippi Delta.

The only confirmed photo of Charley Patton, 1929

The guy uncomfortably staring at you in the photo above is Charley Patton, the Father of the Delta Blues.

Not a lot is definitively known about him. We know Patton was born in Hinds County, Mississippi, possibly near the towns of Edwards or Bolton, possibly in Heron’s Place, some time between 1881 and 1891. He was either Charley or Charlie, his mother was either Amy or Anney, and his father was either a preacher called Bill or a musician named Henderson.

We call him the ‘father’ because he influenced every Delta blues performer who came after him (and because music history is unimaginatively littered with gendered epithets—father, grandfather, mother etc). Patton learned how to play the blues around 1900, and by 1904 he’d taken it on the road, busking all over the Mississippi Delta, something he’d do for most of the next three decades. He was one of the first mainland musicians to play the guitar in the ‘Hawaiian’ way, with the guitar resting on his lap, his fingers perched over the neck, playing the frets like a keyboard, changing keys by sliding a bottleneck or a knife up and down the strings—what we call ‘slide guitar’ today. It’s partly thanks to Charley that we associate the blues so much with slide guitar a hundred years later.

Patton’s distinct style garnered him a lot of disciples on his travels, including big names like Howlin’ Wolf, Son House and Robert Johnson, all of whom would go on to busk themselves. This trend continued as the decades passed: everybody busked. Muddy Waters? Busker. B.B. King? Busker. Memphis Minnie, John Lee Hooker and both Sonny Boy Williamson I and II? Busker, busker, and buskers.

But none of this is new information. I’m not uncovering lost diaries or conducting interviews with their descendants. All I’ve been doing is reading their official bios. And yet, although busking is present in the backstory of each individual musician, I haven’t yet found a blues historian or musicologist (that I’ve read at least) who has looked at busking’s impact in sum.

Which is a shame, because had they done so, they’d have determined that it was, on the whole, buskers who invented the blues.

Bessie Smith, 1925.

If you’re unconvinced, here’s some evidence for you. The Blues Hall of Fame was founded in 1980. Every year since, a few musicians have been added. But for its inaugural year they went big, starting the Hall off by inducting what they believed were the twenty most-influential blues musicians of all time: the who’s-who of the blues. I did a bit of googling, and worked out that nineteen of them were buskers (the twentieth being a pianist).

Take Bessie Smith. She was one of the two female musicians on the list. By the age of nine, Smith was an orphan being cared for by an older sister. Too poor to get an education, she and a younger brother busked for pennies outside the White Elephant Saloon on the corner of Chattanooga’s Thirteenth and Elm streets (that’s not a bad tip, by the way: adjusted for inflation, one cent in 1904 would be worth over thirty cents today.) Smith only started performing on stage at the age of eighteen, and recorded at the age of twenty nine. She was the first blues singer recorded by Columbia (in 1923), launching a career that would see her become the highest-paid black entertainer of her day, and earning her the title of “the Empress of the Blues”.

As a city dweller, Smith was an exception. Almost all the early blues musicians were from poor sharecropping families, the descendants of farm labourers. For them, busking wasn’t just a way of surviving in the town where they lived, it was the tool they used to escape from their homes and from a future of working “from sun to sun, from sun up to sun down” on a plantation. Some of them busked the year they first picked up the guitar, others when they were still children, and others as a way of supplementing their income while supporting their indoor careers.

Imagine, for a second, if Bessie or any of her peers had had to purchase a busking license, or audition in front of an all-white jury, or seek the approval of councils, cops or commercial district managers in order to put a hat down in the street. How many would never have left the farm if they couldn’t busk their way out? How many would have gotten as far as their first record deal? And what would the tone of the blues have been like if its spread had depended on commercial mainstreaming, rather than the efforts of independent, say-what-you-please-and-play-as-you-like troubadours?

Perhaps it’s unhelpful to imagine such things. But those questions kept popping up as my research dragged on. Busking appeared so often in performer bios that I started needing visual aids to help me process it all. Here’s part of a spreadsheet I put together that shows each musician’s childhood (in green), the period in their lives that we know they busked (in orange), and their lives after entering a recording studio (in blue).

Seeing that, perhaps you’ll excuse me for being so surprised that it took the encyclopaedic book, The History of the Blues, the Roots, the Music, the People, a full 116 pages before specifically mentioning street performance. In fact, reading through any of the blues histories that now sit on my bookshelf would lead one to believe that busking was a relatively rare occurrence, rather than the norm.

That is, of course, until the books start talking about the Maxwell Street Market. But even if it is true that we have the market’s amped up buskers to thank for the electric blues—and that’s probably only part true, as musicians were also plugging into amps inside Chicago’s blues clubs at the time—focusing on the amps would miss the best bit of the story: the market was the galactic centre of the blues universe for twenty years.

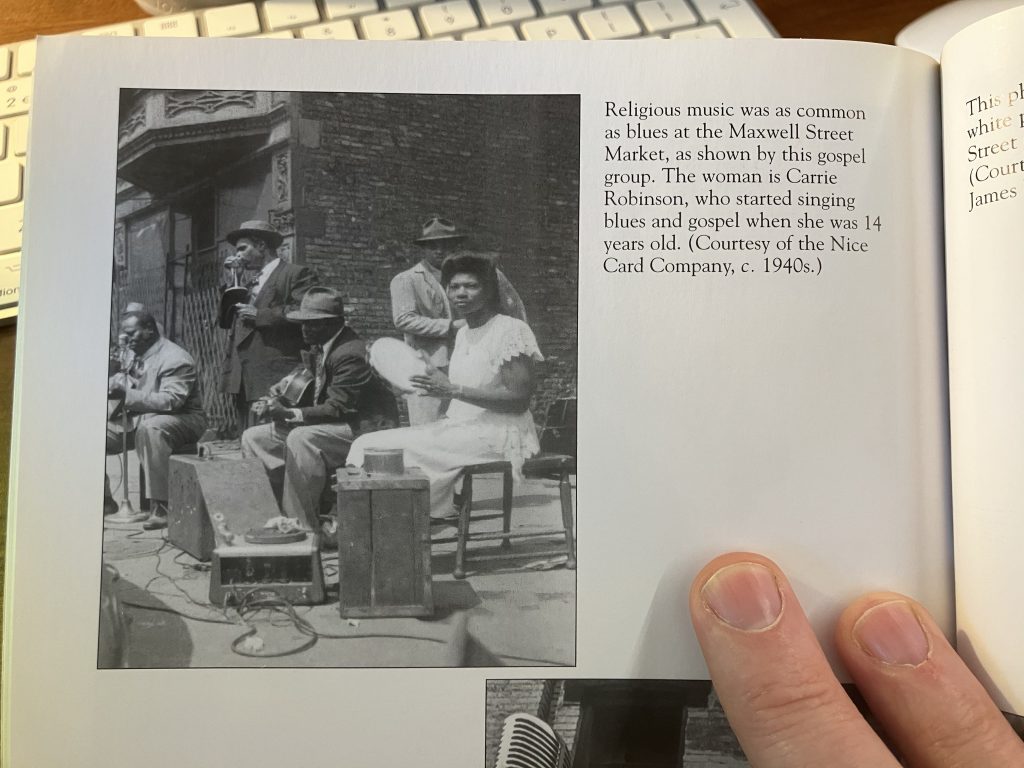

[Incidentally, if you ever get grief from an ‘old school’ busker telling you that, “In my day we didn’t use amplification”, show them the photo at the top of this email, which I pulled from the beautifully written and illuminating book, Chicago’s Maxwell Street, by Lori Grove and Laura Kamedulski. Buskers have been using amps ever since the first mass-produced models hit the stores eighty years ago.]

Chicago only became known for the blues because Delta musicians kept turning up there. Black sharecroppers had been heading north since around the time of the First World War, spurred on not just by their brutal treatment at the hands of white plantation owners, but also because of the boll weevil (which was destroying cotton crops), the Great Mississippi Flood in 1927 and the increasing mechanisation of farm labour. Some six million African Americans left the rural South for northern industrial cities, in what is now known as the ‘Great Migration’.

When they arrived in Chicago, the musicians among them needed a way to get ‘discovered’ before they could get hired to play indoors. So, they’d busk at the Maxwell Street Market, a busy thoroughfare where 70,000 Chicagoans shopped for cheap goods. You can see a little of what that looked like in the photos below, also taken from Grove and Kamedulski’s book.

Maxwell Street Market, c. 1940s

Maxwell Street Market, c. 1940s

Daddy Stovepipe, 1959

Daddy Stovepipe, 1959

Talent scouts would come down to the market looking to hear the new musicians in town. If they liked what they saw, they’d make the introduction to a record label. It’s how a lot of blues legends were first discovered, how they first performed indoors, how they first teamed up with fellow buskers to form bands, how they got their first record deals.

Take Daddy Stovepipe, pictured above. Born in 1867, he started busking on Maxwell Street in 1920. Stovepipe became the eldest-born black performer to be recorded singing the blues in that era, stepping into a recording studio in 1924 at the ripe old age of 57. That also made him the first blues harp player to be put on record. Daddy Stovepipe would continue to busk in the Maxwell Street Market for the next four decades until his death at the age of 96, meaning he’d have rubbed shoulders out there with legends such as Tommy Johnson, Tampa Red, Big Bill Broonzy and many, many others.

My point is, for Daddy Stovepipe and many like him, the streets weren’t incidental. We have no reason to believe that he or his peers viewed busking as just a stopgap measure. Historical accounts only tell us about the views of those who have written the historical record—in other words, we only get to read transcripts written by the institutions, tastemakers and businesses tasked with promoting an art form, people who may have seen the blues’ many decades in the street as an embarrassment to be overlooked, rather than highlighting busking as the very way that the genre was able to thrive. That’s why it’s so often left out of blues histories, not because it’s forgotten, but because historians choose to ignore it.

Perhaps if this was better known—that busking was as much a part of the story of the blues as juke joints, the microphone or the vinyl record—people wouldn’t ask full-time buskers whether they’d ever considered following a more ‘traditional’ career in music. Busking is the tradition. The recording industry is the aberration. And it’s pure madness that we are led to believe otherwise.

Well, all that made me very nervous. I’ve just announced the topic of my book to the world, and revealed a little of what it’s going to be about.

You can let me know if you’re interested in reading more. Also, if you’ve enjoyed this and want to show it to your friends, here’s the link you can share:

busk.co/blog/dont-miss/how-buskers-made-the-blues

Enough words. I’ll finish with photos of blues performers who busked at some point in their careers. These are just the blues musicians I know about! As I’ve written above, an artist’s busking past is often forgotten or hidden from the official record.

Finally, if you liked this email, there’ll be more like it in the future, so sign up here if you haven’t already.

And if you feel like supporting our work, you can do so here: