This post is part of a series taken from research conducted for my upcoming book. If you want to get notified of future emails (and to hear what busk.co is doing next) you can sign up here.

If you missed the first in this series, it’s titled “How Buskers Made the Blues“, and tracks how all the early blues performers were buskers.

Any feedback on the content would be appreciated.

Perhaps the most insidious myth about street performance—or at least the one that is the most widely believed—is that we, the audience, are stupid.

There are two main forms of this argument:

• If the setting is unconventional, we become blind to talent.

• If we are not charged for art, we intellectually undervalue it.

Readers of this website will know, of course, that this is bullshit. We don’t get dumb just because we’ve left the house. In fact, studies have shown that audiences have just as nuanced an evaluation of street shows as they do of indoor ones. Anyone who has spent any time watching buskers will know that generally speaking the most talented performers tend to get the best crowd response.

And yet, “people are dumb” is exactly the message in Pearls Before Breakfast, an article published in the Washington Post in 2007. You may have heard of it: a famous classical violinist played a $3.5 million Stradivarius in the subway. 1,097 people walked past, but very few tipped, and even fewer stood to watch. Joshua Bell, widely recognised as one of the USA’s finest classical musicians, a man that frequently sells out concert halls for hundreds of dollars a ticket, earned just $32 in tips in 43 minutes.

Pearls Before Breakfast was an immediate hit. It won a Pulitzer Prize in feature writing, the highest honour in print media. It was the topic of discussion on all the classical music forums when it came out. It was featured by publications all over the world. Anecdotally speaking, I’ve asked dozens of people about it, and almost everyone had heard of it. Pretty impressive for what is essentially a culture piece in a newspaper printed 16 years ago (like I said, this is the most popular piece of writing ever about busking, which is why I’ve spent so long analysing it).

Also, everyone I spoke to had pretty-much come to the same conclusion: that the experiment showed we are unable to appreciate beauty out of context.

What follows, then, is a deep dive into the way the experiment was set up and its obvious flaws.

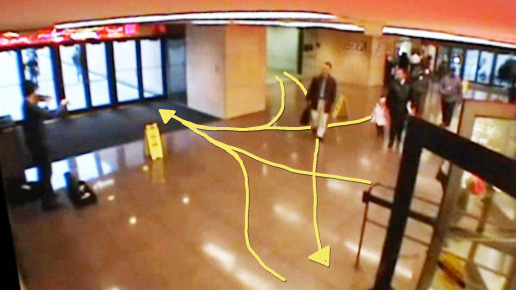

The image above is from the time-lapse that the Post uploaded to YouTube (it’s incredibly pixelated because YouTube only supported 240p resolution videos at the time). At the beginning of his set, Bell is standing with his back to a wall, his case close to his feet, in front of what looks like enough empty space for a decent crowd to form.

The time-lapse shows a different story. The arcade connected a shopping mall, commercial buildings, the subway and the great outdoors, making it a tangled crisscross of invisible paths tracked by people on their well-practiced morning commutes. They turn corners without looking and move with the kind of unthinking uniformity that comes from the perpetual repetition of a daily regimen—everybody clearly knows where to go, how to get there and how not to bump into others along the way.

In my opinion there’s only a single spot in the entire space where someone could stand without getting in the way of passersby, and that was against a wall facing Bell, near the doors on the left-hand side of the image. The reporters knew this as well—it’s why one of them was holding that spot, out of the way, for the majority of the show.

I’ve highlighted the reporter here:

Space wasn’t the only problem. The entire experiment seems intentionally designed to prevent a crowd from forming. It started at 7:51 a.m., just twenty four minutes after sunrise. These were not people with leisure time on their hands. Bell was performing to mid-level bureaucrats in Washington D.C., America’s seat of power, people who’d woken up and left the house when it was still dark outside.

Furthermore, Gene Weingarten, the article’s author, wanted the experiment to focus solely on the music. So, he asked Bell not to be eye-catching. Bell therefore wore drab clothing and a baseball cap low over his eyes, and he didn’t make eye contact with his audience. The only bit of flair mentioned was that Bell sometimes stood on tiptoes when playing high notes, or swayed slightly. Weingarten described this as “acrobatic enthusiasm”. I’d call it “entirely missable to a passing audience”.

So, let’s do as Weingarten wanted, and focus on the music.

For the experiment to make any sense at all, you have to believe the music was objectively beautiful. It’s why Weingarten uses the word ‘beauty’ eleven times in the piece. “Would beauty transcend?” he asks. “Do you have time for beauty?”

Weingarten interviewed several people trying to deduce how, given the obvious beauty of the performance, a crowd failed to materialise. The British author of a book titled Timeless Beauty: in the Arts and Everyday Life suggested that people did recognise its beauty, but walked on regardless. To him, the experiment clearly demonstrated people have “the wrong priorities”. Beauty, he said, “was irrelevant to them”.

Others were more forgiving. A senior curator at the National Gallery said even masterpieces would be ignored if hung in a diner. A Kantian scholar said that Kant thought “viewing conditions must be optimal” to appreciate beauty. In other words, Weingarten explained, “We shouldn’t be too ready to label the Metro passersby unsophisticated boobs. Context matters.”

But in my opinion, the music wasn’t even good, let alone beautiful.

Let’s start with the violin. Weingarten wrote seven paragraphs about Bell’s $3.5 million instrument, saying that “no violins sound as wonderful as Strads from the 1710s”. That may have been the prevailing view in 2007, but multiple double-blind tests have since proven that not only do audiences marginally prefer the sound of new violins, so do the violinists playing them, even in concert hall settings. Given what we now know, it would be absurd to suggest that Bell’s specific violin would have any bearing on the experience of walking through the reverberating echo-chamber where he stood.

Regardless of the instrument, no violinist could have stopped commuters at that time in the morning without accompaniment. ‘Monophonic’ music (where a single note is played at a time, with no chords or harmonies) hasn’t been popular since the Middle Ages, when it was last used in somber religious chants called ‘plainsong’. There is simply no market for solo violin.* Even when Bell went on tour in support of The Man with the Violin, a children’s book written about this very experiment, he was always accompanied by a full orchestra. If Bell wouldn’t inflict solo violin on a paying audience, why should we expect the people passing through this arcade to enjoy it?

Bell also intentionally avoided popular songs, under the logic that this was a test of ‘beauty’, not ‘familiarity’. So, he played six lesser-known works, the longest of which was Bach’s Chaconne. Chaconne is, according to Weingarten:

“…considered one of the most difficult violin pieces to master. Many try; few succeed. It’s exhaustingly long—14 minutes—and consists entirely of a single, succinct musical progression repeated in dozens of variations to create a dauntingly complex architecture of sound.”

Weingarten omitted that music historians also believe that Bach wrote Chaconne during a period of intense grief, after returning home to find his wife dead.

If you want to hear it for yourself, there’s a version of Bell covering that song on Spotify on that same violin. I like a lot of classical music, but to my ears Bell’s playing of Chaconne is far from ‘beautiful’. I might describe it as ‘thoughtful’, but only if listened to in its entirety, so you can hear that musical progression. Broken down into short chunks, it’s utterly indecipherable.

Perhaps we can agree that the music was, at best, ‘an acquired taste’?

Which brings us to a final point about this article, two lies-by-omission so egregious it makes every other detail above inconsequential in comparison.

Of the ten routes through the room in which Bell stood, only one of them took people directly past his case.

Except, not not really, because of the bright yellow caution sign that was stationed right in front of Bell. Almost every single person who could have gone near him instead walked around the sign on its other side.

Weingarten chose to leave out that detail. Presumably, this was noticed by everyone who was there on the day (I counted at least two other journalists in the footage). Surely The Post‘s editors and fact checkers would also have noticed literally the only splash of colour in the room. So, I’ll call it what it was: a conspiracy by multiple journalists to allow and enable Weingarten to put out a better story by ignoring the truth.

Another omission: why didn’t Weingarten mention that the majority of people walking within a coin’s throw of where Bell stood had just come in from the outside, where it was -3ºC (27ºF), not including wind chill. Those people opened a heavy door, so they’d have had just four seconds to connect with the music, decide to tip, take off their gloves and fish around in their heavy jackets for cash, before they’d already passed by.

Weren’t those two details as pertinent as Kant’s views on beauty or the price of the violin? Would the Pulitzer board have been convinced of the article’s value, had those details been mentioned? Who is more to blame for Bell’s arguably (but not definitively) low earnings, the people walking by or the people who set up the experiment?

Weingarten claimed to be asking:

“Can one of the nation’s great musicians cut through the fog of a D.C. rush hour?…In a banal setting at an inconvenient time, would beauty transcend?”

Had he been honest, his question would have been written like this:

“Could a first-time busker—one who is intentionally trying not to be eye-catching or engaging, playing an unpopular study of grief on an indistinguishable violin, situated next to a door and behind a physical obstacle, in a room where there’s no space to stand, during the rush hour, just minutes after sunrise on a cold January morning—create a monophonic sound so compelling that in under four seconds it could convince passersby to go out of their way to tip?”

And you know what the answer to that question was?

“Sort of”. He earned at a rate of $45/hour, under those conditions. Not bad, not great.

I’ll finish here, but first I’d like you to read just a handful of comments posted on various classical music forums at the time:

That they could pass through a bubble of divine music with no recognition, or worse still, to ignore a person who is making an effort to enlighten them….

Soul dead ignorant people. The decline and imminent fall of Western civilisation.

Does not surprise me given the DC locale. However, I doubt the same thing would have happened in NYC, and definitely not in Paris.

All cultural expression is NOT EQUAL. All cultures have an equal opportunity to produce works of genius, but all cultures do not produce it.

Brilliant performance, dumb Americans.

Fantastic description of whats wrong with Washington residents.

That incredible day, no matter where I was going, what I was doing, with a child by the hand, with a hurrying friend, or alone, I would have stopped to listen. Poets do that.

If you can believe it, there’s more! Pearls Before Breakfast gets way worse. And, surprisingly, also way better.

But you’ll have to read about that in my book.

If you’ve enjoyed this and want to show it to your friends, please do! Especially if they’re in the classical music world.

You can also donate! Honestly, some financial help with The Busking Project (by way of small donations) would speed up how quickly I can return to my writing. You can donate here.

Thanks,

Nick

—

*Since I started writing this, it has been pointed out to me by a violinist that she has done several unaccompanied concerts, so there is at least some market for violin. My wife, also, frequently listens to Yo-Yo Ma’s cover of Bach’s Cello Suite #1, which has 245 million plays on Spotify (I think most of them hers). However, I have tried hard and failed to find a ticket online to a solo violin concert—if there is a market for such music, it’s not large.

Donate to The Busking Project

Your donation keeps us in business, and it supports street art all over the world!