A woman with a child beside her approached a balloon artist on the street. It was late afternoon at the Festival of Lights, Chicago’s annual Thanksgiving parade, and the sidewalks were quickly filling up with families. After taking a look at the balloon creations that adorned a sign that the man had set up, a conversation ensued between the two where the woman tried to figure out how much money to give the man. That conversation went something like this:

Woman: “How much do I need to pay?”

Artist: “There is no price. I take donations.”

Woman: “So, like a tip?”

Artist: “It’s a donation. We don’t need any money. Give what you like.”

Despite this claim, a couple minutes later and in response to a man who only handed him a dollar in exchange for a gun-shaped balloon, the balloon artist stared directly at the other man:

“I more than earned that, my friend. I more than earned what you gave me.”

This man later returned to give the balloon artist an additional five dollars.

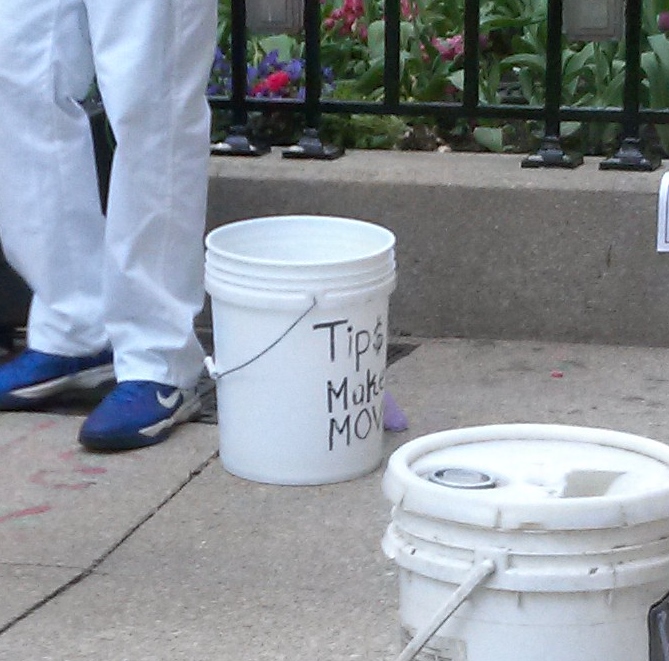

Here, then, is a “donation” – neither a “tip” nor a “payment” – that the performer does not need and yet earned. The work of balloon artists would appear to be the most straight-forward transaction out of the different forms of performances buskers do, the one that most resembles a sale. But in something as seemingly direct as a balloon in exchange for money, this particular performer refused to a payment.

What, then, is the difference between “needing” money and “earning” money? Or, in the labels for cash that this particular artist used, what is the difference between “price,” “donation,” and “tip”?

Let’s start with what the city calls it – contributions.

Chapter 4-244, Article III of the Municipal Code of Chicago – on the regulation of street performers – has a section titled, “Acceptance of contributions” (Municipal Code of Chicago 2013: 4-244-165). A contribution, for one, isn’t a payment.

Payments are legally-binding. When you buy something in a store, you pay the displayed amount to a cashier, and from that moment on the item is yours. As a result, you don’t need to develop any relationship with the cashier.

Contributions, on the other hand, are (legally at least) a choice. If a spectator doesn’t pay for a show she just watched, she won’t face charges for stealing. Legal obligations don’t compel audience members to give money for a show; social expectations do.

We know, as street performers, that the exchange of money after a show is loaded with social tension. It’s why we put so much work into our hat lines, why we sprinkle mention of money throughout our shows, and why we do our best to establish value over the course of a performance – not just that it is worth money, but that it is worth five, ten, or twenty dollars. To get paid, we must build a relationship with our audiences, then define that relationship in a way that makes sense for money to exchange hands.

So what types of relationships?

How we label our money defines the relationships we aim to build – and that’s where words like “donations” and “tips” come in. Their meanings are influenced by the industries in which they’re used more commonly. “Donation” is associated with charity, and “tip” is used commonly in the service industry. Because there isn’t a commonly-used parallel term in the creative industry, street performers pick and choose their own labels in a way that makes the most sense for their individual acts.

The Chicago 10 Man (a living statue) primarily describes his revenue to his audiences as a “donation.” One woman, for example, replied to the 10 Man’s assertion that a picture requires a donation with confusion: “It’s a required donation?! That doesn’t make it a donation!” Her reply only drew a smile from the performer and laughter on the woman’s part as she fished out some cash, and the two of them posed for a photograph.

He went on to explain, “Nobody likes to feel like they’re being sold on something. They wanna sell themselves on the idea first. Donations helps a cause,” which, he said implies that a giver’s “money means something. People like the power of giving. It’s from the heart. All those other words [‘tip’ and ‘payment’] mean ‘You owe me.’ Would you rather shop at the mall with set prices or give a donation?”

The 10 Man here uses “donation” to create a distinct vibe. “Donation” here involves the audience member in the performance itself, creating for the spectator a sense of shared ownership over the show. Even performers who stay away from the word “donation” ask that audience members “support street theater.” The result here is the same: the audience member is asked to participate in the creation of art by becoming a patron of the arts.

The Key is in the “Vibe”

Take Jeremy the Magician from Britain, a Chicago street performer who does not use the word “donations” in his act. Instead, he asks if his audience members are having fun (to which they reply with an enthusiastic YES!) and then follows up that enthusiasm with a hat line that requests that they consider giving him “dollars of fun” at the end of the show.

He describes his attitude towards money as just that – an attitude. And that attitude influences the vibe of his show and, subsequently, the relationship that he has with his audience members.

“One of the things that I try to tell myself when I’m out here is that these people owe me absolutely nothing. I decided to be a street performer. They didn’t ask me to do it. I stand on a corner, I do a magic show…. I have to remember, ok?”

“Cuz if I did a show and I get paid nothing or next to nothing for it, I’m angry and frustrated at these people. If I allow that anger and frustration to brim over, who am I going to take it out on? I’m going to take it out on the people who are going to stop next, who haven’t done anything to me yet, you know? They haven’t stiffed me. They haven’t made me angry. But if I’m communicating that to them, I’m kinda like punishing the wrong people. And then it becomes a sort of self-perpetuating cycle.”

“So the mindset, the head game that you have to have in order to do this to make people stop and stay and pay – and that’s kinda a little mantra of street performers: make them stop, make them stay, make them pay – that’s the goal. In order to do that, I think attitude has a lot to do with it. You know: confidence, presence. If you own the space… this is my office, this is my show, this is where I entertain the people that I want to entertain.”

“If you own that space, then I think that communicates itself in some way to people. It’s one of those unspoken things. I’m sure it comes over in body language or atmosphere or, you know the general kind of vibe that you put off.”

The choice of “donations,” “tip,” “payment,” or even something like “dollars of fun” is therefore really about the kind of atmosphere a performer wants to set for a show, the vibe that he wants to build, and ultimately the relationships that he wants to form.