The following information comes from FOI requests submitted to Camden Council by The Busking Project’s founder, Nick Broad; by Hamish Birchall, a musician and campaigner who worked closely with Lord Clement-Jones on the Live Music Act 2012; and by the internationally recognised busker advocate Jonathan Walker, whose organisation, ASAP, has successfully helped councils across the UK to find mutually beneficial busking policies.

If it helps you, and you want to support our work (and get some insanely good music from street performers around the world) go to patreon.com/busk and subscribe!

(Article continues below)

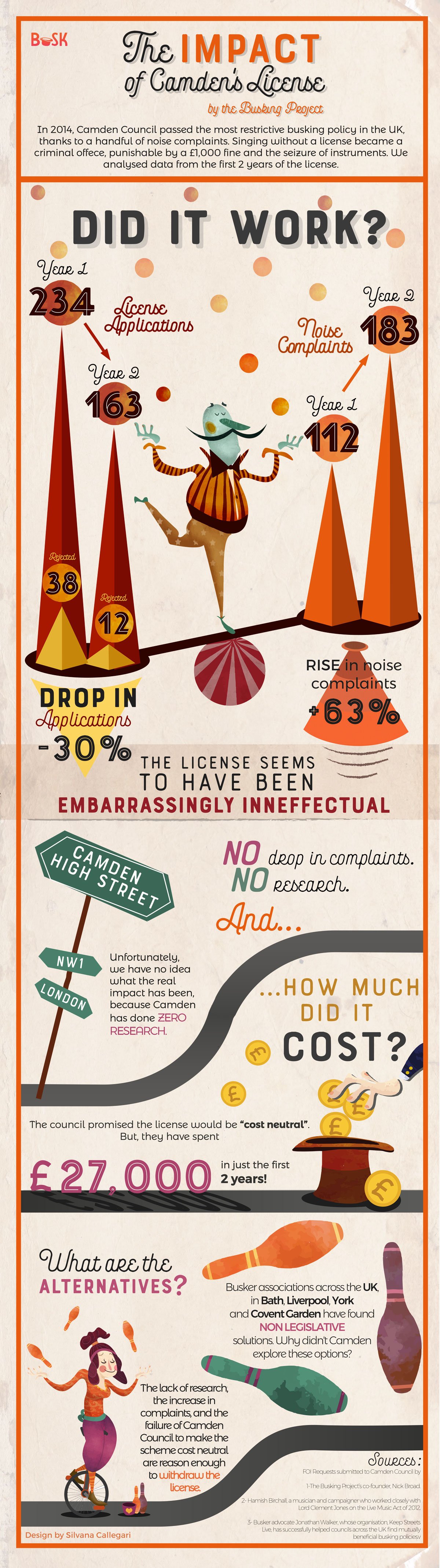

On the 1st March 2014, Camden Council adopted a new licensing system for buskers. The legislation was inspired by noise complaints and consultation responses from residents and the police, and despite the vast majority coming from the central Camden Town area, the license system was adopted across the entire borough. Since then they have prosecuted, to our knowledge, only two buskers (both award-winning, champion beatboxers) for not adhering to the new license.

So, how effective has the license been?

Two years after the new license was put into place, we submitted FOI requests to Camden Council on how the policy was doing. The answer? Not great. In the first two years the council’s new license was ineffectual, expensive and had negatively impacted on Camden’s cultural life. They saw an increase in the number of complaints. And perhaps worst of all, they’ve done zero research into the effectiveness of this needless new legislation.

In other words; they passed the legislation, it has done nothing, and they don’t seem to care.

The Impact of Camden’s Busking License

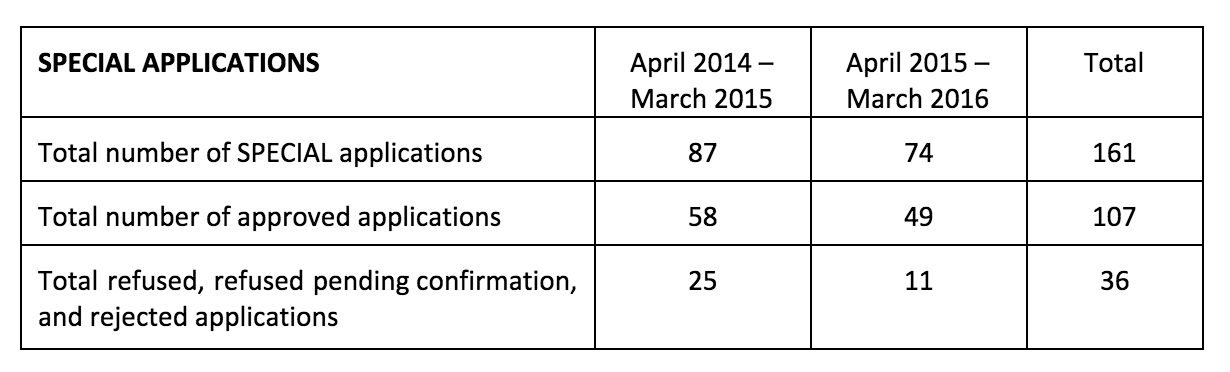

1. In total in 2014 and 2015 Camden Council rejected 50 buskers out of a total of 397 applicants.

% SPECIAL applications rejected and refused: 22.3%

(If the numbers don’t seem to add up, it’s because the council has separated its applicants into categories including “withdrawn”, “new”, “in consultation” and “incomplete”, the nuances of which we don’t understand. So, we’re only counting applications that the council has actively “refused” or “rejected”, when considering the efficacy/impact of their legislation.)

% STANDARD applications rejected and refused: 5.9%

% STANDARD applications rejected and refused: 5.9%

Camden council may claim that the rejection of those 50 buskers makes all the difference for life in Camden. But, if just only 1 in every 8 buskers were problematic, why criminalise the act of unlicensed busking across the entire borough? 1 in 14 priests in Australia have allegedly been involved in the far worse crime of sexual abuse, but you don’t make religion illegal across the entire country. Also, why didn’t Camden Council and police officers use their existing legal powers to deal with the “bad” buskers?

2. There was a 30.3% drop in the total number of busking applications applied for in 2015.

Total Applications in 2014: 234

Total Applications in 2015: 163

% change: -30.3%

This significant drop in license applications either means either:

(a) that both “good” and “bad” buskers were put off applying, or

(b) that performers simply resumed busking without a license in Camden because it wasn’t being properly enforced.

So, either Camden’s license system hurt the livelihoods of not just “bad” buskers but also of professional, skilled entertainers (and therefore the vibrancy of Camden itself), or the license was being ignored. Neither case looks good for Camden Council.

3. There was no reduction in complaints about buskers after the license was installed.

Pre-license, April 2013 – March 2014: 135 complaints (or 3.7% of 3670 total noise complaints)

Year one, April 2014 – March 2015: 112 complaints (or 3.1% of 3594 total noise complaints)

Year two, April 2015 – March 2016: 183 complaints (or 4.9% of 3716 total noise complaints)

Year two of the license saw a 35% increase in the number of complaints compared with the year preceding the license scheme. This is despite a 30% decrease in the number of applications in the second year. We can surmise two things:

(a) If Camden Council put in the legislation based on the complaints about buskers, then by their own standard the license completely failed

(b) If Camden Council’s approval process is supposed to weed-out the noisy buskers most likely to get complaints, their process isn’t working

4. The license running costs were £14,964 in 2014 and £12,380 in 2015.

When the council debated the license they promised that the new scheme would be “cost neutral”. However, they’ve spent over £27,000 on the scheme, and they’ve only rejected 71 street performers.

In other words, it cost Camden Council £380 (the equivalent of a month’s housing benefit) to reject each busker, and the result has been an increase in the number of complaints in the borough.

Note: these costs do not include police time used to enforce the license scheme.

5. Camden Council has done no formal research into the the number of buskers performing in Camden before the scheme or since its implementation, nor on the number of unlicensed buskers.

In fact, their only evidence produced upon request about the effectiveness of the licensing scheme is from a single police officer. The officer claimed that “When buskers operate outside [the conditions of the license], we are likely to receive noise complaints”. If true, the significant increase in complaints about buskers in 2015 would be due to an increase in the number of unlicensed buskers in Camden. And if that is so, the licensing system has failed in every respect.

Camden has done no research into the impact the license scheme on the busker community – artists who rely on performing in Camden for their livelihood – or Camden residents themselves. This lack of care and consideration means the council could be maintaining a policy that has negative impacts for Camden Town. The statistics certainly don’t back up the idea that it is doing any good.

In Summary

The lack of research, the increase in complaints, and the failure of Camden Council to make the scheme cost neutral are reason enough to withdraw the license.

The many arguments against the policy

Below we have summarised the case against having needlessly prohibitive legislation criminalising street performance in Camden. This case was put forward to Camden Council by Jonny Walker and other busker advocates, including a representative of the Musicians Union. It was, of course, ignored by Camden Council.

The Political case against Camden’s Busking License

The biggest political objection to the creation of a licensing regime is that it creates a new criminal offence of ‘busking without a license’ and an obligation to enforce the law against people who aren’t actually causing any nuisance. This means kids busking for 15 minutes down at the dock could get a criminal record for playing music, in one of London’s artiest boroughs.

Also, many complaints about street performers are likely to be people informing the police about buskers who aren’t causing any real issue beyond the technical offence of ‘unlicensed busking’ – which has a knock on effect of consuming police time.

The Financial Case against Camden’s Busking License

In a fiscal environment where in 2012-2013 there were £83 million pounds of cuts in Camden, it is hard to justify spending £380 on stopping each busker from playing their instrument. When making severe cuts to spending on your residents, it’s unwise – maybe even immoral – to create a new set of rolling costs.

Okay, £27,000 for a new license is relatively small against the total number of cuts, but why would Camden Council spend all of this time, effort and money on persecuting street performers, while the borough is in an obvious state of financial emergency – especially when you consider that they make up less than 5% of the total noise complaints in the borough!

The Legislative Case against Camden’s Busking License

Camden Council already has the ability to enforce against buskers who are causing a nuisance, without incurring the additional costs of maintaining a licensing regime, processing complaints against unlicensed buskers and prosecuting unlicensed buskers who aren’t causing a nuisance.

These powers have been strengthened by the (controversial but powerful) Anti-social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014, which allows councils to issue community protection notices against persons who have a detrimental impact on those in the locality through behaviour that is persistent and unreasonable.

Previously, section 62(1) of the Control of Pollution Act 1974 makes it an offence to operate a loudspeaker between 9pm and 8am. And there are a range of powers under the Public Order Act 1986 and the Anti-Social Behaviour Act 2003 (Section 2 – Social landlord’s powers, Section 4 – Powers to disperse groups, Section 6 – Excessive noise and graffiti), that could be used to deal with any “anti-social” busking.

The fact that they have criminalised street culture, prosecuted and given criminal records to talented young artists, discriminated against wind and percussion players through a complex tiered licensing scheme and damaged Camden’s reputation as a place which nurtures art and music are other arguments against the policy.

Camden Council’s Weak Evidence to support the policy

Camden Council felt the need to draft new legislation because of 104 complaints about street performers between October 2012 and September 2013. The complaints hardly warranted to council’s response:

- The complaints were made by just 58 people, making up 1 in every 3,400 residents (or, including and this doesn’t take into account over five million annual visitors who come to Camden to soak up the cultural vibrancy of the borough).

- ¼ of the complaints came from just two people who were obsessively anti-busking.

- Over half of the complaints only mention that a busker is present, without identifying why the complaint was being made

- The complaints made no distinction over whether the busking lead to undue inconvenience, or a safety risk or noise nuisance.

- The complaints suggest that a few people in Camden just don’t like “busking” in the widest sense.

- The majority of complaints listed refer to busking being “loud”, or “amplified”, without any detail of effect or context.

- The busking complaints constituted less than 5% of the borough’s total noise complaints (it is a vibrant borough!)

- The complaints were almost exclusively in Camden Town, and yet the entire borough of Camden was licensed under this scheme.

(Not to mention, of course, that since implementing the policy the council has done no research to find out what the impact of their new policy has been.)

The Case for Alternative Options

Quick communication between authorities and buskers in case of problems is important and useful. A database with contact details of “not behaving” buskers is can be sufficient to tackle the problem. Non-legislative solutions have been found in Liverpool, York, Bath and many other major cities where the council has felt the need to manage the busking ecosystem.

The council didn’t research whether better dialogue with local street performers – nor whether setting up a busker association – would address problems without the need for legislation.

If a few bad buskers were spoiling it for everybody, Camden Council could have cracked down on the small number of buskers who were causing a real noise problem under existing legislation. Other councils have done it – why not Camden?

The council didn’t exercise existing powers of enforcement that would address problematic buskers and ambiguous cases, instead arguing that current legislation made it too difficult to deal with street performers.

It may be easier to regulate performers once you have a license in place, but “ease” is not a reason to criminalise something.

In Short

Perhaps Josie Appleton, the director of the Manifesto Club and author of “Officious – Rise of the Busybody State”

“As a Camden resident, I’m shocked that the council has spent rate-payers’ money on such an illiberal and ineffective system. Camden’s street music is one of the defining features of the borough. This nit-picky licensing system is squeezing the life out of the borough’s cultural scene and should be scrapped immediately. Buskers should not have to pay and ask council approval before picking up a guitar and bringing music and life to London’s streets.”

And a picture paints a thousand words…

DOWNLOAD THE FOI RESPONSES HERE:

https://blog.busk.co/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/EIR-Response-20530540.pdf

https://blog.busk.co/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/EIR-Response-20532087.pdf

https://blog.busk.co/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/EIR-Response-20566157.pdf

https://blog.busk.co/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/FOI-Response-20529398.pdf