But, oh, the power it has over our lives…

To legally busk in the city of Chicago, you must go in person to City Hall, Room 800.

Room 800 houses the “Department of Business Affairs and Consumer Protection: Business Assistance Center.” Seriously. You go up to the person behind the counter who asks you why you are here. When you tell him that you are here to get a street performer’s license, he gives you a form to fill out and points to a ticket machine. You take a ticket, sit down to wait your turn, and take a deep breath as you take stock of where you are and how you got here.

When I got there, I realized pretty early on that it was a suit and tie kinda place. But while I didn’t exactly fit in, I didn’t stand out too starkly either. A brief chat with one of the city clerks hinted at the experiences of other buskers who had walked through these doors. He remembered vividly how a man covered all in silver and a woman coated in gold had come in not too long ago; he told them to wash the makeup off their faces so they could get photographed for their street performers’ licenses.

In the eyes of the law, street performers are ostensibly in the same legal category as the rest of the city’s businesses. And yet, the city clerk’s ability to recall the other street performers who had come through here made it clear that we stand apart from the rest. What would it have been like, I wondered, to attend that meeting where a group of suit-and-ties decided that street performers are the type of people whose affairs should be housed at the DBACPBAC?

When, finally, it was my turn, and they call me up by flashing G620 across a screen, I approached the counter to pick up a form. This form is an application for one of three licenses: “Peddler,” “Food Peddler,” or “Street Performer.”

And in case you’re confused about what the three licenses mean:

- A peddler sells… stuff.

- A food peddler sells… uh.. food.

- And a street performer sells… er…

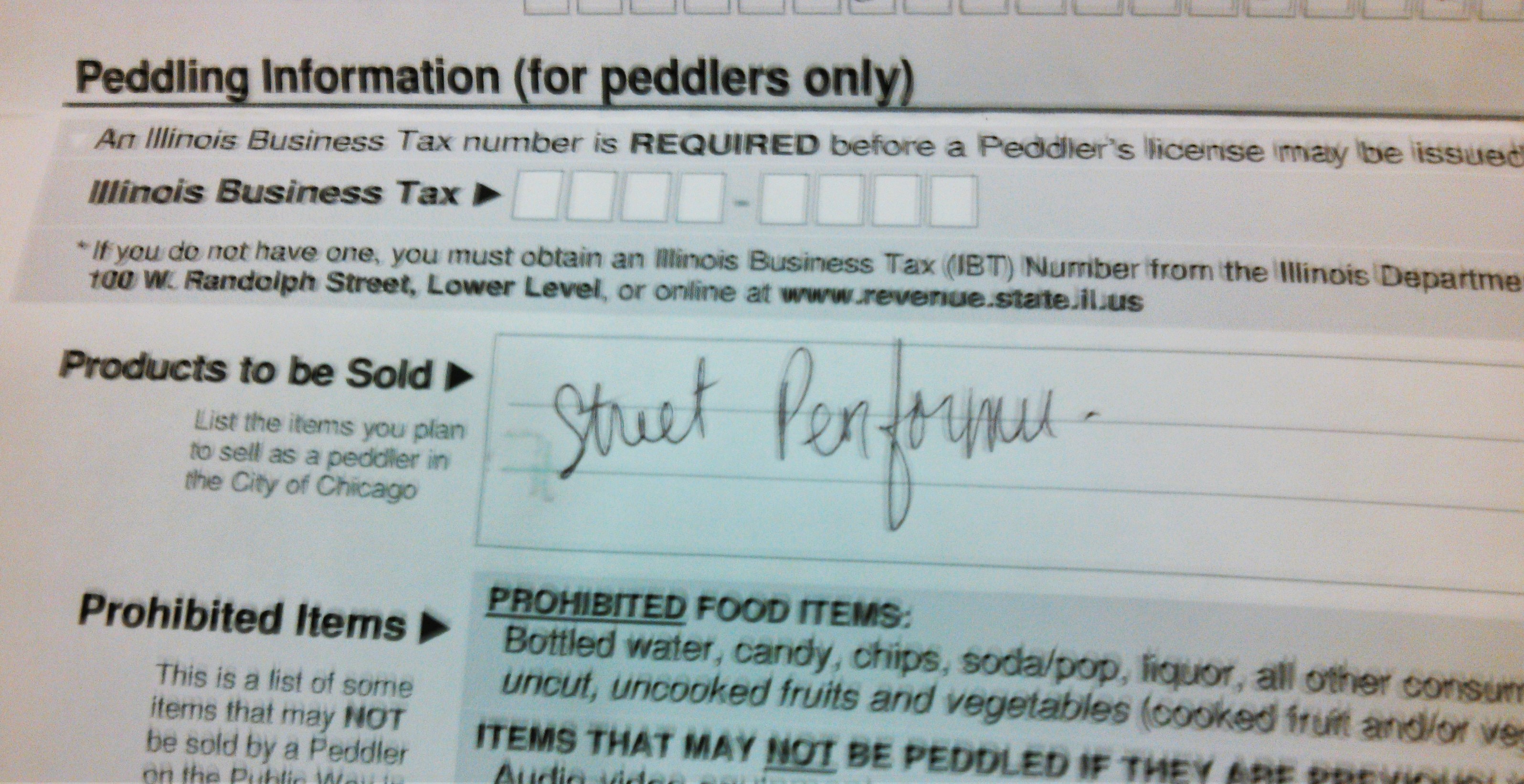

Really. That’s what the clerk wrote on my form when I tried to get my permit back in March of 2014.

I don’t know why she wrote what she wrote – whether it was standard procedure or an off-the-cuff decision to try and fill in that box (because as we know, in bureaucracies, all boxes must be filled).

But one thing was clear: here, in its attempts to create distinctive kinds of licenses – all under the domain of the Department of Business Affairs and Consumer Protection – lies the government’s attempts to tax businesses, regulate movement, and enforce the specific regulations that differentiate one category of person from another.

But what category of person is a street performer?

Take a closer look at the last photo, and you’ll notice that the title of this section is “Peddling Information (for peddlers only).” Immediately beneath that, the document asks that people applying for a Peddler’s License provide their Illinois Business Tax number.

Of course, as a street performer, I didn’t need to put a Tax number in. But, the city does want to know who you are, where you live, when you were born, and how to contact you.

Why?

Maybe they don’t expect street performers to make a lot of money. Maybe they’re just acknowledging the impossibility of keeping track of our earnings.

What, then, is the purpose of licensing? Why did I have to go to City Hall, fill out their forms, and pay a $100 fee to get this?

Why does the city of Chicago have a licensing process for street performers?

True, the City of Chicago can earn money through the licensing process itself, a process that needs to be renewed every two years for a $100 fee each time. The significance of licensing, however, becomes apparent in the Municipal Code of Chicago.

In chapter 4-244, a section on “Street Peddlers and Street Performers” formally defines the following three terms:

“Perform” means and includes, but is not limited to, the following activities: acting, singing, playing musical instruments, pantomime, juggling, magic, dancing or reciting.

“Performer” means any person holding or required to hold a street performer permit under this chapter.

“Public area” means any sidewalk, parkway, playground or other public way located within the corporate limits of the City. The term “public area” does not include transit platforms and stations operated by the Chicago Transit Authority or the Metropolitan Transportation Authority.

(Municipal Code of Chicago 2013: 4-244-010)

These terms legally define who performers are, what kinds of activity they do, and – in part, through the definition of a “public area” – where they can perform.

Visibly labeling performers by requiring them to “carry and display a permit on his or person [sic] at all times while performing in a public area” (Municipal Code: 4-244-163) enables performers to busk while, at the same time, serves as an acknowledgement of the regulatory authority that restricts them from performing at certain places and times.

On top of that, any anonymous call to the police – a noise complaint from a nearby retailer, for example – means that the performer has to move, have their permit rescinded, or face arrest. Indeed, as I was about to depart Room 800 (aka the DBACPBAC), the city clerk handed me a Street Performer Fact Sheet (a more concise, layperson’s version of the Municipal Code of Chicago), suggested that I read it over, and said that a police officer’s order overrides anything that is written in the document.

Since police officers can ask a street performer to stop performing or move at any time (whether as a result of an anonymous complaint or according to the whims of a given officer), the Street Performer’s License does not actually grant the performer any rights at all.

Its purpose is, instead, to give law enforcement a reason to approach street performers and to act as a starting point for their interactions, both positive and negative.

Licensing, then, is a means of control – of regulating space in favor of local businesses and residents who can be depended upon to pay taxes. As one street performer’s fiancée (and a Chicago–based teacher) was telling me:

“People would complain, whether people are residents or the businesses. And the complaints will go back to the police of course because they go to the meetings. They have to please the Michigan Avenue Association. It’s a lot of wealth. You have to keep them happy. They would make the complaints to the police, to the city, so on and so forth, and they would take action.”

Government regulation is thus less about legitimizing buskers through the granting of licenses than it is a means of controlling the streets. The supposed fear is that street performances make noise and obstruct traffic. This fear makes it so that, even if a street performer has become a regular fixture of the city (or a cultural landmark, even), street performers are always in danger of losing their performance spots.

Regulations and arbitrary enforcement of those regulations thus make street performances appear inherently transient. This transience, a manifestation of the view of street performances as nuisance, is an argument against the work of street performers as socially valuable – and, in effect, against a perspective of street performance as real work.

The response, from the point of view of Chicago’s buskers, is telling: in the patter of their performances, the regularity and frequency of their shows, and the descriptions they give of what they do, the street performers I spoke with insisted time and time again on the status of their work as work. This insistence I shall explore in future posts – so keep an eye out for me again next month here on the Busking Project.

Donate to The Busking Project

Your donation keeps us in business, and it supports street art all over the world!